Don’t Blame Gen-Z. It’s the Registration Gap.

A false narrative circulating for years proclaims that young people don’t vote. As a result, campaigns limit their outreach to young voters, young voters feel less connected to the national debate, and government is less responsive to issues that disproportionately affect young voters. Even organizations focused on increasing voter participation mobilize fewer resources to get out the vote campaigns targeting young voters.

But we’ve got it all wrong. Young adults who are registered to vote actually turn out at rates approaching those of older adults in presidential election years. The problem is not that young people don’t vote. The problem is that many fewer of them are registered to vote than their older counterparts.

The opportunity to turn out more young voters by registering more of them is staggering. Based on 2016 Census data, 55 percent of 18- to 24-year-old citizens were registered to vote, and 78 percent of them actually voted. And while 87 percent of registered older Americans turned out to vote--a 9-point margin over 18- to 24-year-olds--the registration gap was almost double that with 72 percent of older Americans registered to vote. Had 72 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds been registered and turned out to vote at the same rate they did in 2016 there would have been 3,470,372 more votes cast by that demographic. And had 18- to 24-year-olds been registered at the same rate as 65- to 74-year-olds, they would have cast over 5,200,000 more votes without increasing their turnout rate at all. That’s almost 4 percent of all votes cast in the 2016 election in which the margin of victory in battleground states was often narrower.

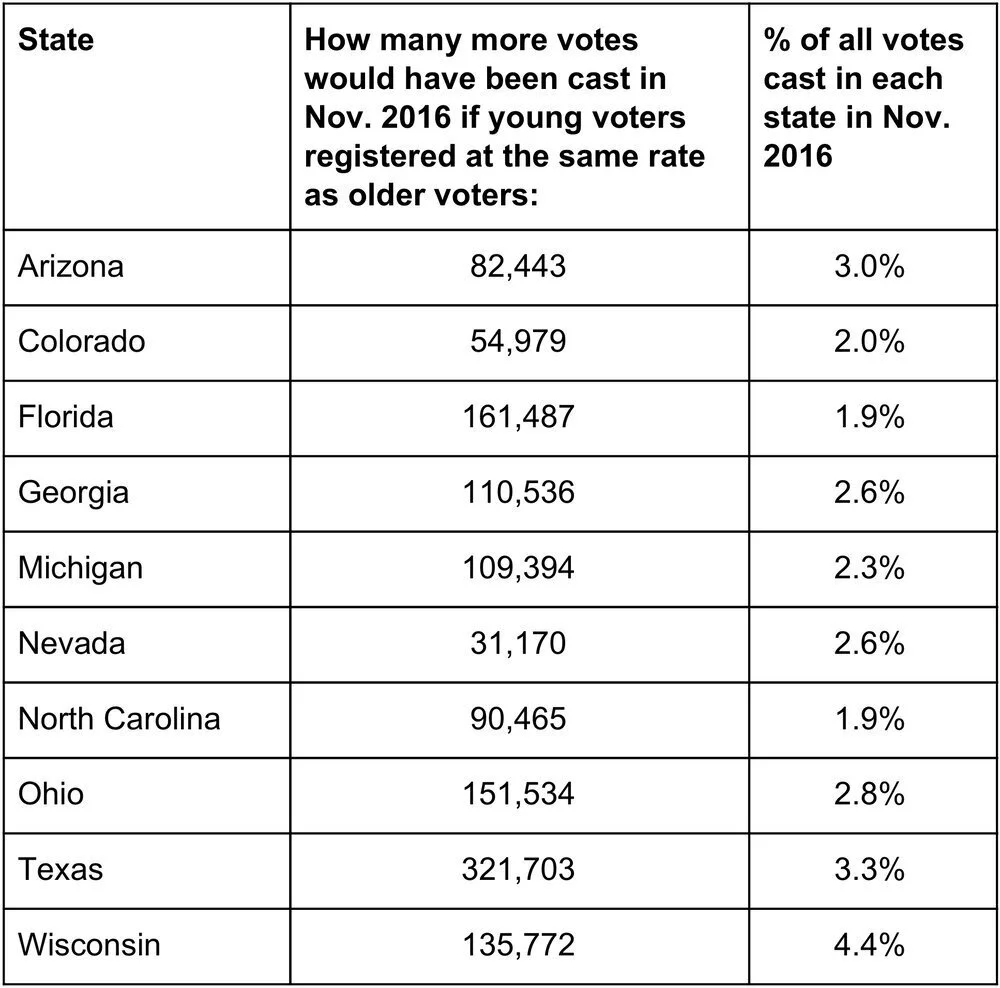

The effect of increasing registration rates among young Americans in swing states is equally striking. Applying the average registration rate among voters over 24 to the population of 18- to 24-year-old citizens and assuming young voters turned out at the same rate as they did in 2016 shows that many more votes (equalling a substantial percentage of all votes cast in 2016) would have been cast by young voters:

And states that are unlikely to swing between the political parties also present tremendous opportunities for young voters to make a difference in state and local elections. For example, in Utah, registering 18- to 24-year-olds at the same rate as older voters could have yielded as much as 6 percent of all votes cast in 2016, and in Kansas, the impact could have represented 3.5 percent of the 2016 vote total.

A few caveats: The Census Bureau data for 18- to 24-year-olds has a nationwide margin of error of 0.9 percent and a margin of error of 3.3 to 8.8 percent for that category of data for the states listed above. And some believe that young adults who are motivated to vote will register, thus dampening the effect of merely registering more young adults to vote. But many young adults list “never asked to register” as a primary reason they are not registered to vote. And the 18- to 24-year-old population has increased since 2016, meaning that whatever gains are made in registration rates will yield more voters. Finally, young voters showed us in 2018 that they are more motivated to vote than ever, so the gains from higher voter registration should yield even more impressive results in the 2020 election.

Given the number of razor-thin margins that decided the 2016 presidential election, the registration gap between 18- to 24-year-olds and all other age groups is significant. And given the ease with which we can register more teens while they are still in high school, particularly in the 34 states that allow pre-registration or registration before the age of 18, closing the registration gap is a no-brainer. To accomplish what seems to be an easily attainable goal, however, state legislators, local politicians, school board members, principals, and parents must demand and support nonpartisan high school voter registration efforts.

The Civics Center supports these efforts and, in the meantime, encourages students to organize peer-to-peer voter registration drives to close the gap. When young adults vote at numbers more reflective of their proportion of the electorate, politicians, government, and others will take note.